When I give talks on evangelization, I can feel great energy in the room as we look at the Church’s documents on evangelization. Evangelii nuntiandi, Evangelii gaudium, and a host of quotes from popes, thinkers, saints, and atheists get people fired up and ready to go out into the streets to live and speak the gospel. While it is a great feeling to see Church leaders getting fired up, that enthusiasm can often fade when I begin to share current statistics. Real, cold-hard facts that give black and white numbers to peoples’ hunches and experiences about the dramatic loss of numbers experienced in our churches.

Among these statistics, there is one that breaks my heart more than any other. Among Christians, Catholic teens are the least likely to pray daily. It breaks my heart because of the richness of our Tradition in terms of personal prayer, contemplation, and mysticism. I know many evangelicals and when they begin to dive deeply into personal prayer, they begin to read Catholic writers and spiritual masters. Merton, Rohr, Theresa of Avila, and John of the Cross, Meister Eckhart, Thomas a Kempis, and Julian of Norwich: these are the great writers and mystics in our treasury that my evangelical friends discover with great delight and about whom many Catholics remain ignorant.

The second vexing statistic is that the Catholic Church has the greatest rate of attrition among Christian Churches. Even worse, among those who still identify as Catholic rather than ex-Catholic, only 16% are highly involved in their Churches. Only our Episcopalian friends have a lower rate of high involvement at 13%.

The third statistic, and it sounds like a contradiction, is that Mass attendance does not equal Mass attendance. By this we mean that taking your children to Church every Sunday is no guarantee at all that they will continue to go to Mass in college and in the later young adult years. Of all factors, the one factor rating as the highest guarantor of ongoing participation in the life of the Church is daily personal prayer.

It seems that the dots are quite clear to connect: 1) the greatest guarantor of ongoing religious affiliation is daily prayer 2) Catholic teens are the least likely to pray daily 3) the Catholic Church has the highest rate of attrition among Christian Churches and ecclesial communities. May I posit a “therefore”?

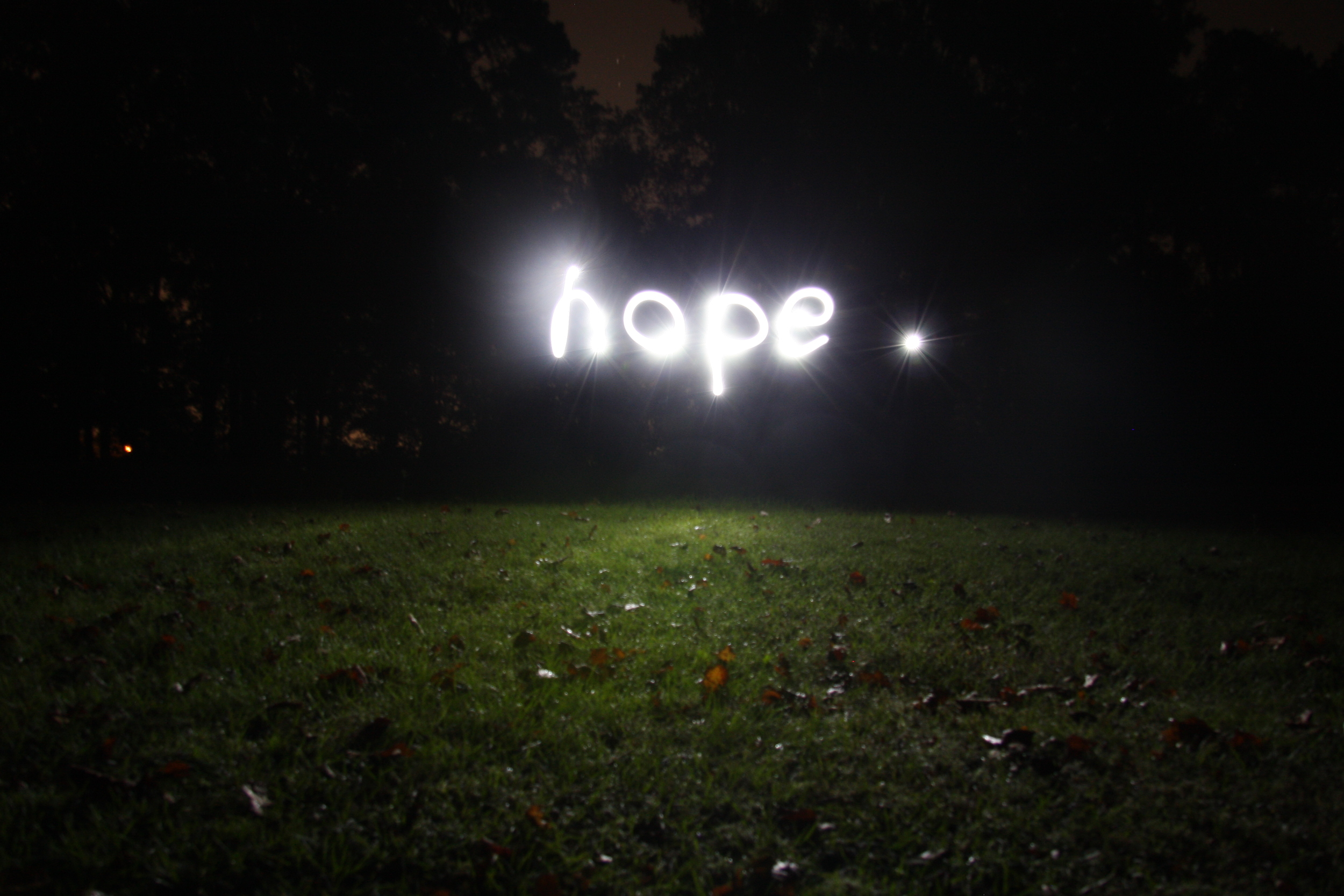

Therefore, the greatest thing we can do as youth ministers and as parents is to foster a daily prayer life among our teens. I don’t know why we haven’t done a better job at than we have. When I was in the parish, I lead awesome group prayer. Candles, incense, music, lighting, an authentic proclamation of the scriptures: the weekly prayer services at our youth nights were stunning. Yet, I don’t recall asking my teens about their personal prayer life. I wanted to give them experiences. I wanted to instruct them in the Church’s teaching, but did I give them what they needed to develop a daily personal prayer life?

Those of us who follow the lectionary have all of the tools to help our teens do so. We don’t just stick a bible into teens’ hands and say, “Here, start reading.” The Church gives us a rhythm of seasons and daily readings from Scripture. We have an inherent guide through the bible. Even more than that, the Church also gives us lectio divina, a four-step method for praying with Scripture:

- Use your body. Read the passage.

- Use your mind. Think back through your day at school and what happened with your friends and family today. What does the passage mean to you based on what you’re going through in life?

- Use your feelings. Now that you understand the meaning this passage has for your life, what does it make you want to pray for?

- Use your intuition. What does God say to you in return?

We have to remember that our faith is not an ideology. Our faith is in a person, Jesus the Christ. It is he whom we encounter, fall in love with, follow, and to whom we conform ourselves. I feel like those of us in youth ministry are pining for the one, single program, movement, or innovation that will stop the bleeding of our youth and young adults from our churches. Our mission trips, lock-ins, leadership training conferences, efforts at liturgical renewal will all only make sense if our teens are rooted in a person that they encounter on a daily basis. Back when I was a parish youth minister I discovered that good youth ministry is about asking the right questions. Perhaps the best question we can ask is, “How was your prayer time last night?”